On a Friday evening, and shortly before the deal between Musk and Twitter fell, Musk shared a few tweets. One of them, the latest, was a comment on a post by an Italian data analyst, Andrea Stroppa, who supported Musk’s thesis with his own research. He went so far as to speculate that fake accounts on Twitter were between 12% and 14%, publicly winning the praise of Tesla’s number one.

In the last few hours, Stroppa published a series of tweets better detailing the methodology used and once again backing the claim that “SPAM or FAKE on Twitter is 10-14%”, a number largely higher than the 5% rate declared by Twitter CEO.

Some of the tweets are incredibly useful to better understand what may have created so vastly divergent numbers in the estimate, and one peculiar one may be the key to understand an underlying methodological error that may easily account for the difference.

Meet Botometer

Researchers used Botometer for several reasons, but primarily to assign scores to Twitter accounts associated with the likelihood of being automated, of in Twitter words “displaying inauthentic behaviours”.

Botometer’s algorithm is trained on thousands of combinations of factors to decise whenever accounts are automated or not, made by the research group’s own team of human coders. This training data set helped Botometer algorithm approximate human coding decisions.

Botometer uses over 1,000 pieces of information about each account, including measures of sentiment (mood), time of day, who the account follows, the account’s tweet content and its Twitter network, and these variables are used in a “random forest” machine learning algorithm. Then attributes a bot score to accounts on a scale of 0 to 1.

Sounds easy. It is not. By far.

While Botometer remains an astounding piece of research and is vital in spotting POTENTIALLY automated accounts, and while it can be incredibly precise, the margin of error even in idyllic conditions is far too high to be used in econometric estimates. And can lead to severe miscalculations.

How precise is Botometer?

An incredible work titled “The False positive problem of automatic bot detection in social science research” published on PLoS gives us insights on the matter:

We (..) show in (..) that Botometer‘s thresholds, even when used very conservatively, are prone to variance, which, in turn, will lead to false negatives (i.e., bots being classified as humans) and false positives (i.e., humans being classified as bots). This has immediate consequences for academic research as most studies in social science using the tool will unknowingly count a high number of human users as bots and vice versa.

“The False positive problem of automatic bot detection in social science research” published on PLoS

I strongly encourage you to take a look at the full research, but many factors are cited that may negatively influence variance, and one of the most important is Twitter being multi-language and – for example – Botometer is extremely inaccurate in identifying german bots: if 0.76 is used as a threshold, 41% false-positive humans will be amongst the accounts classified as bots.

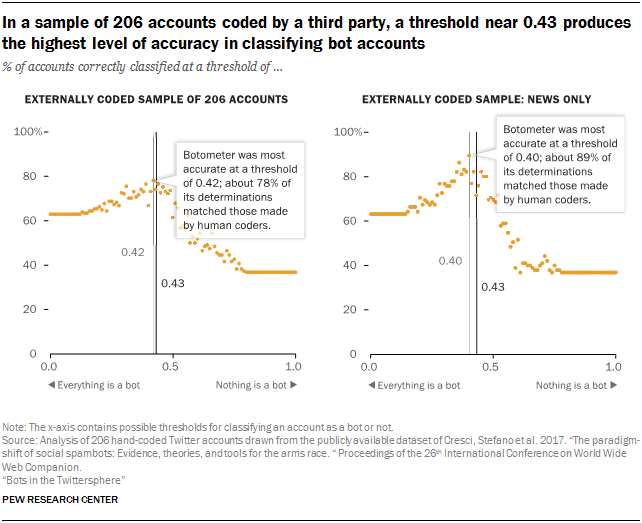

In addition to this, even one of the most regarded Internet Research institutes, the Pew Research Center using Botometer for research has not been able to achieve a precision higher than 78%.

The Center team that tested the accuracy of all thresholds of the Botometer using externally coded data, found a threshold of approximately 0.42 maximized accuracy of the classification system – very close to the 0.43 originally uncovered by Botometer researchers. The maximum accuracy in this set of accounts was approximately 78%.

It stands to reason: Botometer team itself in “Online Human-Bot Interactions: Detection, Estimation, and Characterization” measure the accuracy of a classifier trained on the honeypot dataset to 0.85 AUC.

Does a 78-85% precision figure matters? Yes it does.

What went wrong?

The difference between the 5% SPAM figure cited by Twitter CEO and the 12-15% figure stated by Stroppa could simply be within the margin of error of the algorithm used, that does not retain a 100% precision score.

And there is more: BOTS are NOT Fake Accounts. The classification of SPAM/FAKE ACCOUNT itself is a very difficult task, because you could run a completely automated account without it being SPAM (eg. automated tickers, RSS feeds for a publication, or even automated services like Whale Alerts). Botometer researcher estimates for the bot population range between 9% and 15%, but it should be clear by now that those figure are not depicting SPAM, but just bots that may fit perfectly within the TOS.

And please, let me say again: this is not a “fault” of Botometer, an incredible and spectacular algorithmic rendition of a task – spotting automated account – that is sometimes difficult to understand even to humans. Those researchers are in my eyes near-divinities and a, 85% of precision is in my eyes keen to performing miracles.

But, and this is totally IMHO, one should be very careful in stating price-sensitive statistics without being completely sure of their methodology, as one could easily fall into libel.

About me

I am adj. Professor in Corporate Reputation & Business Storytelling, in CyberSecurity and in Data Driven Strategies, I founded The Fool, the leading Italian company of Customer Insight to increase Value and Reputation, and co-founded the Legal-Tech company LT42 for Legal Data-Automation, and I’m Partner of 42 Law Firm where Lawyers lead Digital Transformation..

I am Chairman of PermessoNegato APS, the no-profit NGO that provides technological support to victims of Non-Consensual Pornography (Revenge Porn) and co-founder of Hermes Center for Transparency and Digital Human Rights.

I’ve been Future Leader IVLP of the US State Department under the Obama Administration in “Combating Cybercrime” program, I am editorialist, Keynote Panelist, PodCaster for Forbes, and I host a daily show, named Ciao, Internet! where I discuss about Algorithms and Rules that govern Machines and Humans.

I still don’t how to play the piano, I’m buddhist by vocation, reducetarian by ethics and Nerd.